Note: This is a 3-part series on what advocates can do to provide comment on the draft Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices. Part I provides background on the document and why it’s important to comment. Parts II and III will focus on bicyclist- and pedestrian-specific elements of the draft MUTCD.

By Don Kostelec

January 17, 2021

The Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices. It’s a mouthful but it greatly influences how our streets are operated and managed. MUTCD is why a speed limit sign in Florida looks the same as a speed limit sign in Idaho (don’t mention Oregon’s speed limit signs). It’s what guides how a pedestrian signal is timed for people to cross the street.

A draft of the 11th edition is now published by the Federal Highway Administration for public comment. It is the first update to the manual since 2009. Comments are due March 15, 2021, but many agencies are requesting an extension.

A lot has changed in the realm of active transportation design in those 12 years. A lot has changed in the flow of information and impact of online technology, including social media. This means the 11th edition of MUTCD is going to be the most publicly-viewed and publicly-vetted version in the 85-year history of the manual.

Advocates for Vision Zero and safe streets have a chance to be heard as they never have before. In my work, through training workshops like the Looking Glass Academy, we give advocates, planners, health professionals, engineers, consultants, and others insight into MUTCD to help make a better argument for safer streets.

If all you do is tell a traffic engineer “I don’t have enough time to cross the street,” then it’s easy for them to ignore and cast your concerns aside. It’s very different if you tell the traffic engineer “This is a 70-foot wide crossing and we only get 15 seconds to cross. Based on the MUTCD rate of 3.5 feet per second for pedestrian signals, we should have more time.”

In this post, I provide you with the links and what to look for when reading and commenting on MUTCD. Engineers have for too long thrived on keeping the public at arm’s length when it comes to MUTCD. Don’t fall for the black box excuses. Yes, there are some technical elements of the 700-page draft document that may not be quickly understood; but that is the exception and not the rule. Many of MUTCD’s contents are easily comprehended by the person who just wants to get where they are going safely.

The version I recommend you access first is the “mark-up” version on the FHWA site containing the proposed text version, found at this link. It shows the changes from the 2009 version. It is 784 pages long, but easily searchable in a PDF reader program. The clean text version is 700 pages long but does not show changes. It is easier to read.

- Note this link is a direct download of the PDF file labeled “mark-up”: https://www.regulations.gov/contentStreamer?documentId=FHWA-2020-0001-0038&attachmentNumber=1&contentType=pdf

The federal portal for the draft MUTCD is at this link and you can access already-submitted comments at this link. I always try to see what State DOTs and other public agencies submit for comments as it gives you insight as to what their focus and bias may be. The comments from individuals are also entertaining, but voluminous.

If you’re on a city or state advisory committee, consider discussing draft MUTCD and how your group can provide comment on it. Ask your agency’s transportation or traffic department to provide their own summary of draft MUTCD as an agenda item, then also request that you receive a copy of any comments they submit. You may also alert elected officials to the draft MUTCD and see if they will request their staff provide a work session on the draft MUTCD. They should know their engineers are reviewing and providing comment on it.

In my first read through of it, I find it discouraging that pedestrian deaths have risen dramatically since 2009, yet the sections of the draft MUTCD pertaining to pedestrians remain relatively unchanged. For bicyclists, there are major changes in this version as the influence of organizations like NACTO are clearly being heard.

Background

MUTCD is one of those “bibles” of traffic engineering. It’s a dinosaur of a document that first appeared in 1935 as a way to standardize what we now call traffic engineering practices.

Chapter 1A of the draft MUTCD spells out its purpose:

- “To establish national criteria for the use of traffic control devices that meet the needs and expectancy of road users on all streets, highways, bikeways, and site roadways open to public travel.”

Chapter 1A then spells out how this purpose is achieved through goals for promoting national uniformity of traffic controls devices and consistency in installation of them; providing basic principles for traffic engineers to use in the design of streets; and promoting safety and efficiency through appropriate use of traffic control devices.

“When we advocate for safer streets, the MUTCD may be cited by engineers as an obstacle for making the changes needed — sometimes correctly, sometimes incorrectly,” said Eileen McCarthy, a retired attorney and member of Washington, DC’s Pedestrian Advisory Council. “As lay advocates we may not be able to understand every technical detail in the MUTCD, but we can develop a general working knowledge of it and use it for our own purposes and we can work with experts who are more adept with the technical details.”

It is important to distinguish what MUTCD is used to regulate versus what other transportation documents like the AASHTO Green Book are used to regulate. A key part of the title of MUTCD is “Traffic Control Devices.” Not everything in the roadway environment is a traffic control device (TCD). The 1935 edition of MUTCD defined TCDs as:

- “All signs, signals, markings and devices placed or erected by authority of a public body or official having jurisdiction, for the purposes of regulating, warning or guiding traffic.”

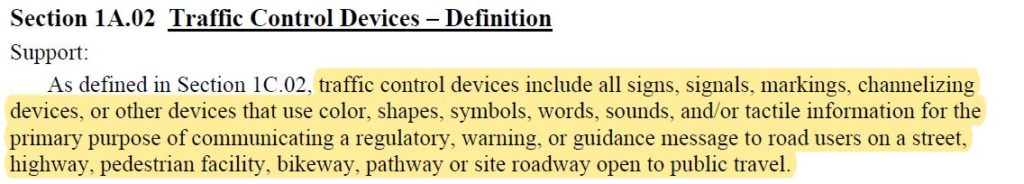

Much of that definitions carries through to the definition in the draft 11th Edition, shown below.

A traffic signal is a traffic control device. A stop sign is a traffic control device. A pedestrian push button is a traffic control device. A sharrow is a traffic control device (insert joke here).

A protected bike lane is not a traffic control device, therefore not part of MUTCD. A general purpose travel lane is not a traffic control device, therefore not part of MUTCD. You will not find guidance on things like the acceptable range of width of these lanes in MUTCD. You will find guidance on those lanes are striped or marked and how the movements of users of those lanes are managed at intersections via TCDs.

There is oftentimes an assertion by engineers that MUTCD is developed to include elements based on some type of sacred science. It is not. I could write an entire series of posts on this false claim. The best example I know of to prove what’s in MUTCD is not based on science is when Bill Schultheiss documented how inclusion of a requirement for pedestrian signal heads when signalized intersections are installed for motorists was shot down by a simple show of hands from a group consisting primarily of white male engineers sitting in the Amen pews.

MUTCD Standards?

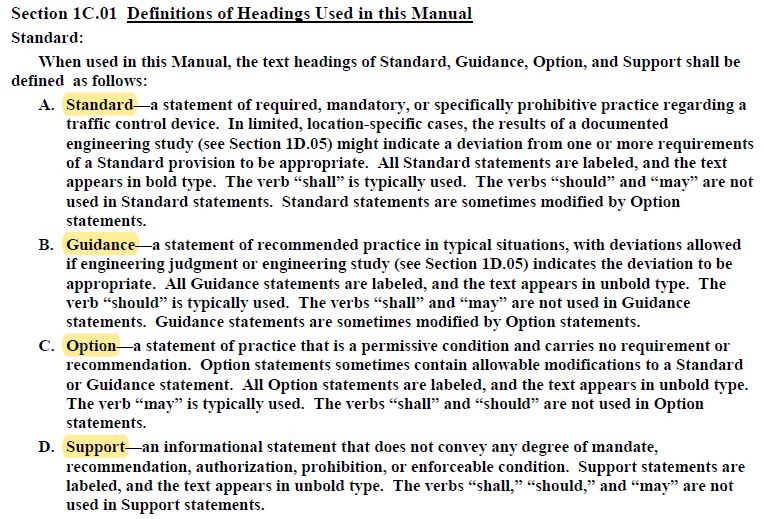

MUTCD is oftentimes referred to as “MUTCD standards,” which is it not. MUTCD is a collection of several statements on traffic control devices, some of which are standards. There is a hierarchy of statements in MUTCD, as shown below from Section 1C.01.

Standards are easy to identify in the document as they are accented with bold text and use the word “shall.” As the image above shows, Guidance statements use the word “should” while Option statements use the word “may.”

Those standard/shall statements are generally viewed by engineers as inflexible in how they are applied. While there’s some merit to that, there is also flexibility allowed by licensed professional engineers to use their engineering judgment to solve a site-specific issue. It is generally recognized that no manual–even one as voluminous as MUTCD–can define every condition for traffic controls across the United States. In acknowledging this, Section 1D.05 states:

- “Site-specific conditions might result in the determination that it is impossible or impractical to comply with a Standard. In such a case, a deviation from the requirement of a particular Standard at that location might be the only possibility. In such limited, specific cases, the deviation is allowed, provided that the agency or official having jurisdiction fully document, through engineering study, the engineering basis for the deviation.” (Page 33 of the “Text-Clean” version).

This doesn’t mean you should openly expect an engineer to throw a standard/shall statement out the window. But do know they can deviate from it by using their engineering judgment and documenting why. Knowing flexibility is inherent in MUTCD helps advocates advance their cause when a stubborn professional may try to fend off requests by citing something like “MUTCD says it’s a standard, so I can’t help you.” Oftentimes you will find they interpreted a guidance or support statement as a standard despite it not being so.

What to Look For

“Like Brigadoon, the MUTCD is shrouded in mystery and is rarely open for public comments,” Eileen McCarthy told me in an email exchange. “We have a unique opportunity now to tell FHWA what we think.”

When conducting a search of the PDF, I found the word “pedestrian” is used 830 times in draft MUTCD while “bicyclists” is used 118 times. “Safety” is used 157 times. The word “standard” is used 1,383 times. Try searching these words or those that interest you to find the pertinent passages.

- Chapter 1: Start by reading this section, which is 36 pages long. Part I is important as its sets the stage for why and how MUTCD is used. Most of those pages include definitions, which are easy to skim through.

- Chapter 2 is a 264-page snoozer, focusing on things like sign colors, sign shapes, sign placement, etc. A word search will help you get through this section to find pedestrian and bicyclist features. This section will become more meaningful when the related sign graphics are added. It’s always interesting to note how state DMVs have removed the sign tests from driver’s license renewals despite there being dozens of new signs added each time MUTCD is updated.

- Chapter 3 begins on page 300 of the clean text version and focuses on lane markings. Chapter 3C addresses crosswalks and there are major changes in terms of how crosswalks are better defined in this version. Chapter 3H outlines colored pavements, including aesthetic treatments for crosswalks and green bike lanes.

- Chapter 4 addresses traffic signals of all types, with substantial content on pedestrian and bicyclist signals.

- Chapter 5 is new for autonomous vehicles. This is what prompted this update in the first place. You should comment on it and be skeptical of FHWA’s motives in drafting this section. It appears to be written by the auto industry. A positive feature is Section 5B.06, which spells out the shortcomings of autonomous vehicles and supports protected bike lanes. Watch closely how the comments from state DOTs are written about this section. I suspect they’ll oppose this passage.

- Chapter 6 pertains to construction zone treatments, which are called “Temporary Traffic Controls.” This has the sections related to pedestrian and bicyclist access, including ADA requirements.

- Chapter 7 addresses school zones and has many important passages on these critical areas. This section is very important for advocates to read.

- Chapter 8 is for the transit wonks. Section 8E addresses sidewalk and pathway grade crossings of rail crossings.

- Chapter 9 is for the bicyclists. It is 37 pages long, beginning on page 660 of the clean text version. Page 691 and 692 address sharrows, known to traffic engineers as “shared-lane markings” (insert digital toilet paper comment here).

Who to Watch?

Five minutes of perusing draft MUTCD will reveal that no single traffic engineer can possibly know what all 700 pages contain. I know a couple of savants who probably come close.

I view MUTCD as the Winchester Mystery House of engineering guidance. It has been amended so many times without a complete rebuild that it has many competing and contradictory elements. We can’t blow it up and start over quite yet, so we have to make do with what it is.

Here are some key people to follow on Twitter as the comment period unfolds:

- Eileen McCarthy: @myrna38717

- Bill Schultheiss, Toole Design Group: @schlthss

- Peter Koonce, Portland BOT: @pkoonce

- Ken McLeod, League of American Bicyclists: @kenmcld

- Barb Chamberlain, WSDOT: @BarbChamberlain

Your local area may have staff or consultants who are members of the National Committee on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (NCUTCD), which provides guidance to FHWA on developing MUTCD. The latest publication of the NCUTCD membership list is from 2018 and is accessed here.

If you know of others, please send me their info and I’ll add them to the list: @kostelecplan. Also tag me in any interesting findings you uncover as you read the draft MUTCD and use the hashtag #DraftMUTCD. Happy perusing!