The 12 Days of Safety Myths

December 15, 2018

by Don Kostelec

Standard, /ˈstandərd/, noun: a required or agreed level of quality or attainment.

Required level? Or agreed level? That’s a big difference in how we interpret what exactly a standard consists of in the street design realm.

“AASHTO standards” is a phrase used all the time when transportation agencies write their reports, produce their public meeting materials, and ultimately use the term “standards” as a way to deny safer engineering for people who walk and bike.

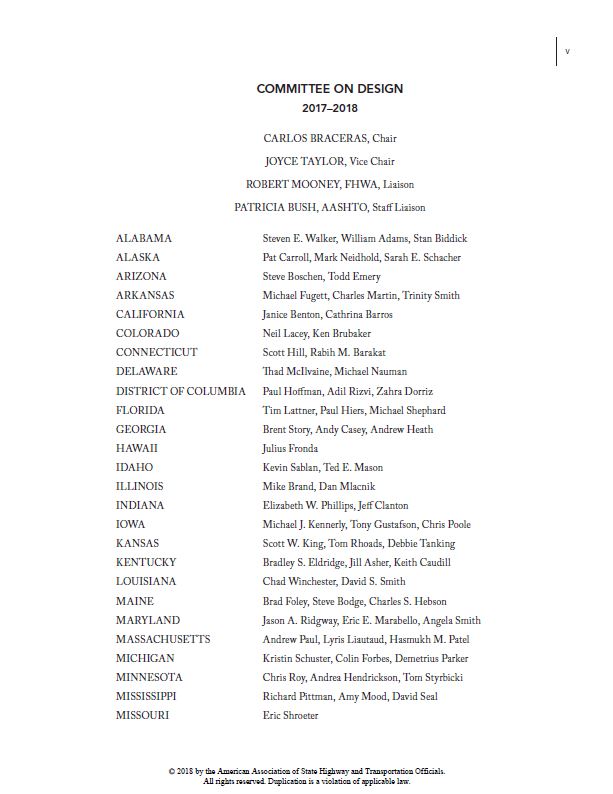

AASHTO–the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials–is essentially the national organization of state DOTs. All 50 state DOT executive directors serve on AASHTO’s Board of Directors. AASHTO is funded by them. State DOT engineers serve on many AASHTO committees and develop AASHTO design standards guidance.

AASHTO’s latest version of the Green Book (2018)

AASHTO produces many engineering publications, most notably their “Green Book.” The Green Book’s formal title is A Policy on Geometric Design of Highways and Streets. AASHTO, whose Board of Directors is comprised of all of the directors of the 50 state DOTS, just published the 7th edition of its Green Book .

When you hear someone refer to “AASHTO standards,” they are most likely referring to the Green Book. To the layperson interacting with a transportation engineer the use of the term “standards” can be intimidating. Politicians with limited knowledge of transportation are even more reluctant to question something if an engineer says it’s a “standard.”

Nearly everyone, especially the engineers, use the definition of standard that aligns more with it being a “requirement” rather than an agreed to level of treatment. Pitching elements of the Green Book as a requirement allows engineers to deflect questions about their decisions. On the contrary, if they used the term “standard” to mean something mutually agreed upon, that would open up the design to a true community-based approach.

But the interesting part is this: Not even AASHTO refers to its Green Book as a standard. It’s guidance. The Preface of the Green Book’s 7th edition includes the following paragraph (emphasis added):

- “A Policy on Geometric Design of Highways and Streets provides geometric design guidance based on established practices that are supplemented by recent research. This document is intended as a comprehensive reference manual to assist in administrative, planning, and educational efforts pertaining to design formulation. This policy is not intended to be a prescriptive design manual that supersedes engineering judgment by the knowledgeable design professional.”

Guidance. Reference. Not intended to be prescriptive. Hmm. That’s not what your engineer told you, eh?

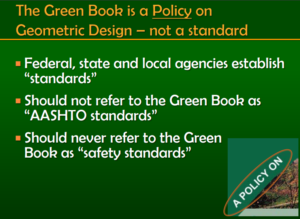

A presentation done by the Kentucky Transportation Cabinet correctly notes that the Green Book is not a standard and should not be referred to as a standard.

You should print that paragraph, laminate it, and put it in your wallet to carry to project meetings for the inevitable moment when the engineers act as if their understanding of the Green Book is that it is some sacred text.

The Preface also states:

- “Designers should recognize the joint use of transportation corridors by motorists, pedestrians, bicyclists, public transit, and freight vehicles. Designers are encouraged to consider not only vehicle movement, but also movement of people, distribution of goods, and provision of essential services.”

Shall we? We must!

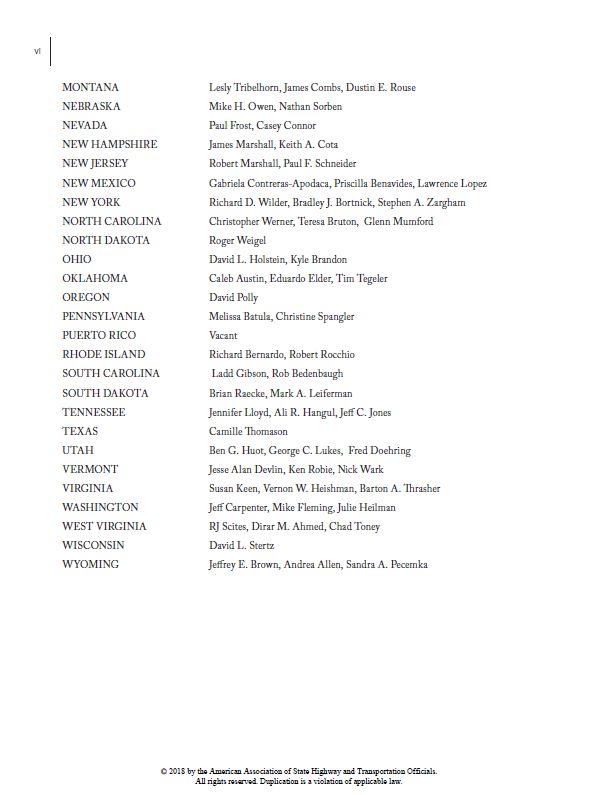

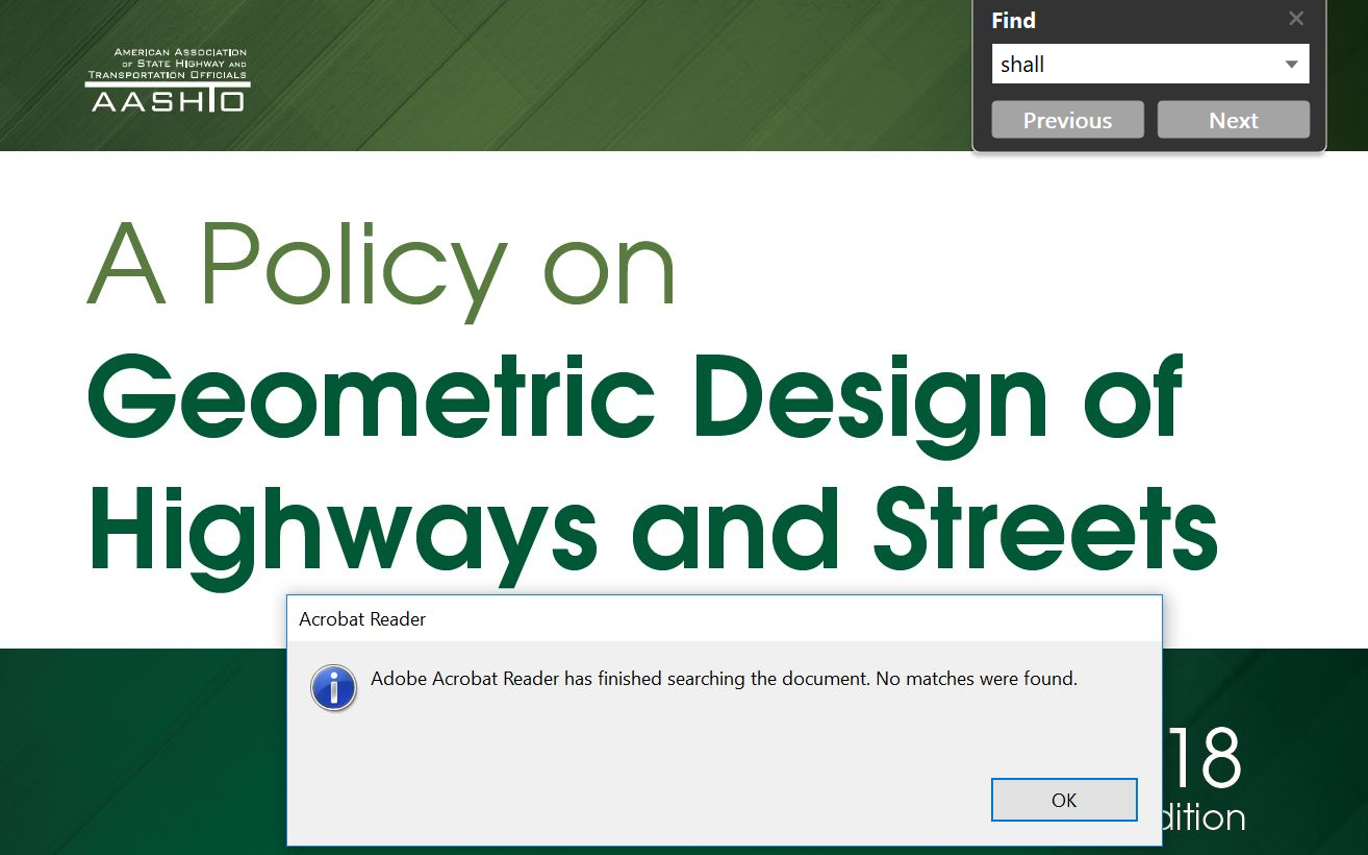

If something was a true “standard” the sense that it is required it would stand to reason that a publication like the Green Book would contain many sections that use the word “shall” or “must.” Those two terms are traditionally viewed as making an action compulsory. “Shall” is the word normally used in transportation policy to denote a mandatory element.

The PDF file of the Green Book is 1,048 pages long. Below are the results of a search for the word “shall” in that PDF. It doesn’t appear among the 1,048 pages.

The word “must” is, however, used in the Green Book. Section 1.8 is about Design Flexibility. It states:

- “The word ‘must’ is used in this policy only when specific design criteria or practices are a legal requirement…For example, ‘must’ is used to describe practices related to the development of pedestrian facilities that are accessible to an useable by individuals with disabilities.”

More Green Book gold from our friends at Kentucky’s DOT.

It gets better.

That same paragraph goes on to say:

- “(T)he design criteria presented in this policy are not fixed requirements, but rather are guidelines that provide a starting point for the exercise of design flexibility.”

Laminate that, too!

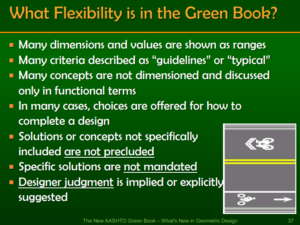

The fact is the design parameters where active transportation interests tend to ask for flexibility are those where the AASHTO Green Book provides a set of ranges for design dimensions. Frankly, it’s not all that technical when you start to read through it.

For example, Section 7.3.3.2 addresses Lane Widths on Urban Arterials (page 601 of the 1,048-page PDF file, if you’re keeping score at home). A common request from active transportation interests is travel lanes narrower than 14-feet or 12-feet wide in order to provide room for bicycle lanes or sidewalks within a constrained right of way footprint. How many times have you had that request refused. Here’s what The Green Book says:

- “Lane widths on through-travel lanes may vary from 10 to 12 ft. Lane widths of 10 ft may be used in more constrained areas where truck and bus volumes are relatively low and speeds are less than 35 mph. Lane widths of 11 ft are used quite extensively for urban arterial street designs. The 12-ft lane widths are desirable, where practical, on high-speed, free-flowing, principal arterials.”

Nothing, NOTHING, about that is as prescriptive as some engineers will try to tell you when denying your request for narrower lanes.

Dear AASHTO: Make it free! Make it public!

Want a PDF copy of the Green Book? It’ll cost you $310. A paperback is $388.

AASHTO’s other publications and costs are:

- Guide for the Planning, Design and Operation of of Pedestrian Facilities (2004): $115 PDF, $143 paperback.

- Guide for the Development of Bicycle Facilities (2012): $162 PDF, $203 paperback.

- A Guide for Achieving Flexibility in Highway Design (2004): $27 PDF, $34.

It’s understandable that costs for printing a book would merit charging for it. But with PDFs there’s no reason these publicly-funded documents should be kept under lock and key. My PDF version of The Green Book is password protected and I must use my AASHTO login to access it.

Your local transportation department probably has copies of it. They might let you borrow it. If you’re part of an advocacy organization, try a fundraiser to purchase copies of these guide books. You’ll put them to good use and the engineers hate nothing more than when you come to a meeting with a hard copy of one of these guides.

Another approach is checking your library to see if it has a copy of the Green Book or any other publications. If not, suggest they get copies for their reference library. You may have to make photocopies of it to take to meetings, but it would be a cheaper way to make it accessible.

After all, the development of the AASHTO Green Book is paid for by your tax dollars. AASHTO is floated by state DOTs and the United States Department of Transportation. State DOTs are the AASHTO biggest customer, contracting with them to do training and bridge safety work.

The bulk of AASHTO’s revenue ($62 million of $74 million in total revenue) comes from what their audit report calls “Technical service fees and product revenue.” That has to be derived largely from state DOT contracting for their efforts. AASHTO reported $3.5 million in publication sales revenue. Membership dues netted them $2.7 million.

AASHTO’s 2017 Audited Fianancial Statement shows they received more than $9 million from USDOT that year, including nearly $1 million in federal funds for general AASHTO “Operations Support Activity.”

Another interesting find is AASHTO’s 2013 Tax Form 990, which revealed that their Executive Director had a salary of $332,000 for working only 37 hours a week that year. AASHTO’s Director of Policy and Director of Intermodal Activities each made more than $200,000. Their Director of Publications made $144,000. Five other AASHTO staff members made more than $150,000 in salary in 2013.

(Side note: AASHTO’s Audited Financial Statment from June 2017 revealed what’s called a “Control Deficiency.” According to the accounting firm that did the audit, AASHTO has a “lack of knowledge regarding the new requirements” for reporting the scheduled expenditure of federal funds. The report notes AASHTO failed to meet federal reporting requirements. They failed to meet deadlines for quarterly reports on expenditure of federal funds. LOL. You’d think an agency run by other agencies that manage billions of dollars in federal funds would know how to report on the use of federal funds. And, yes, I’m the nerd who reads Audited Financial Statements of highway agencies! Back to the Green Book…)

Below are two pages from The Green Book. They list the individual state DOT representatives who contributed to development of this guidance.