The 12 Days of Safety Myths

December 22, 2018

By Don Kostelec

In the carol “The 12 days of Christmas,” the gifts are grander and grander with each passing day. I’m not sure I’ve accomplished that for you in this series, but I hope the time you spend reading them is well spent.

The goal was to help you dispel the common myths you hear from transportation agencies with regard to safety. The guidance isn’t as sacred as they want you to believe. The safety tips don’t make much sense when you look at the research. Even the research isn’t as clear cut as we would all like it to be.

I want you to be the drummers drumming to advocate for safer streets. I want you to be the pipers piping to influence changes in policies and practices. I want you to light the coals that keep the engineering lords a-leaping when they try to deny your requests.

The Forgiving Road

When you delve into the issues, you realize that neither AASHTO nor FHWA are the bad guys. Their works promote a very flexible mindset, and have for many years. Lane widths are one such example.

Sadly, it’s at the local and state level where the prevailing national “guidance” becomes a “standard,” thus a barrier to safety, all in the name of shaving a few seconds off a driver’s experience. The tendency is to give drivers the most forgiving road they can possibly design.

Ben Ross, a citizen activist who has better perspective than most transportation pfoessionals, made this statement in a tweet on November 18, 2018:

- “Breaking the law to save time? If you’re a speeding driver, traffic engineers try to keep you safe. If you’re on foot far from the crosswalk, tough luck.”

What Ross is getting at here is what engineers term the “forgiving road.” The forgiving road is one that forgives the mistakes motorists make. Wanna speed because you’re late? Our roads accommodate that to a certain degree. Not so much when the pedestrian is running late and needs to get to a bus stop on that same road.

The forgiving road concept emerged in the early era of engineering for freeways and interstates, where it makes the most sense if a motorist deviates from their line and leaves the lane. It gives them time and space to correct the vehicle. Even more ironic is this concept has elements of what we’d today call Vision Zero, accounting for human mistakes in the design of roadways.

The problem comes when we start to applying interstate highway concepts to surface streets within cities and towns. That’s when the concept, as applied on interstates, falls apart. Gary Toth, PE, worked at New Jersey DOT for 30 years (I think that’s correct). He now does work for Project for Public Spaces and penned this piece on the forgiving road. Chuck Marohn of Strong Towns call them “stroads.”

Toth references Kenneth Stonex, who helped generate the early interstate design concepts. “What we must do is to operate the 90% or more of our surface streets just as we do our freeways… [converting] the surface highway and street network to freeway road and roadside conditions,” Stonex testified.

Lane Widths

It is this forgiving philosophy that leads to engineers doing their best to justify wider travel lane widths on urban streets. Give motorists more room to recover if they make a mistake at high speeds. That’s the philosophy. No one else seems to matter.

The new version of the AASHTO Green Book provides for a range of motor vehicle travel lane widths on arterial and collector roadways. I addressed the underlying elements of the Green Book on the 6th Day of Safety Myths.

The Green Book first addresses lane widths in a general sense in Chapter 4 Cross-Section Elements.

- The lane width of a roadway influences the comfort, operational characteristics, and, in some situations, the likelihood of crashes. Lane widths of 9 to 12 ft are generally used, with a 12 ft lane predominant on most high-speed, high-volume highways…A 12-ft lane width reduces the cost of a shoulder and surface maintenance due to lessened wheel concentration at the pavement edges. A 12-ft lane also provides desirable clearances between large commercial vehicles traveling in opposite directions on two-lane, two-way highways in rural areas.”

The last two sentences are important in understanding AASHTO’s intended audience: State DOTs. The engineering within states is typically for two-lane rural highways noted here, four-lane highways that have shoulders instead of curbing, and interstate highways. Those are all reasonable situations to have 12-ft vehicle travel lanes.

The Green Book has sections on arterials, collectors and local roadways in urban areas. AASHTO notes that both urban arterial and collector lane widths may vary from 10 ft to 12 ft, and the Green Book repeats that earlier statement about 12 ft lanes being used primarily for high-speed, high-volume principal arterials.

It gets better.

AASHTO then states in section 7.3.3.2 on Lane Widths for urban arterials:

- “Under interrupted-flow operating conditions [read traffic signals, pedestrian signals, frequent driveways] at low speeds (45 mph or less), narrower lane widths are normally adequate and have some advantages…Reduced lane widths…may help in reducing operating speeds, and allow shorter pedestrian crossing times…Arterials with reduced lane widths are also more economical to construct and produce less stormwater runoff.”

One paragraph! That’s all you need to start the discussion on narrower lane widths in your community. It’s all there, even justification for the ever-present “we don’t have any money” excuse you get from transportation agencies. I wish they’d mention that less pavement yields less life cycle cost, too Otherwise, you might call it the perfect paragraph on lane widths.

AASHTO repeats that range of lane width for collectors (Chapter 6), noting industrial areas with heavier truck volumes are where collectors would have 12 ft lanes.

Local Streets are addressed in Chapter 5, with support for lanes of 9 to 11 ft, specifically noting that 9 ft lanes can be used in residential areas. Unfortunately they caveat this with “where the available and attainable width of right-of-way imposes severe limitations.” Who the hell is building brand new residential streets in existing, developed areas?!?

This language in the new Green Book is nothing new. The widths were the same in previous Green Books, so don’t let your local engineer act as if they haven’t had time to review and consider this. The problem is they want to default to the maximum Green Book width for arterials and collectors, all while trying to give people who walk and bike the minimum width for their space.

The 10-ft Lane Conundrum

This is another instance where AASHTO is on the side of the walking and bicycling advocates, but we have to be careful in making that request. It is very situational and if done incorrectly can create some challenging conditions for bicyclists in bike lanes adjacent to 10 ft travel lanes.

Let’s start with the support for 10 ft lanes. AASHTO’s Guide for Achieving Flexibility in Highway Design states “there is less direct evidence of a safety benefit associated with incrementally wider lanes in urban areas, compared with other cross-sectional elements.” They also say “drivers tend to be more comfortable traveling at higher speeds on roads with wider lanes.” This is AASHTO saying that the freeway’s forgiving road concept with regard to lane widths doesn’t apply on urban streets.

AASHTO notes in the Green Book that the outside lanes of a multi-lane road–your typical four-lane arterials–should be wider than the inside lanes since that’s where trucks and buses tend to operate. It’s also not a silver bullet. 10 ft lanes in the absence of other vertical design features to narrower the field of vision of drivers probably won’t have the effect on safety and speed that we want.

(Don’t you love the crack seal/public art pattern?)

On a busier arterial, a 10 ft travel lane immediately adjacent to a 4 ft bike lane leaves virtually no room for error by someone operating in either lane. That’s why you don’t default to the minimum dimensions for each lane.

If you have a 10 ft travel lane and 5 ft for a bike lane, then I prefer to stripe a one-foot buffer between the two to act as a type of flex space for the rare large vehicle whose mirrors may slightly overhang the buffer. I also like that option because it helps narrows the visual field for the driver with the striped buffer. The extra cost of the paint in the buffer is the argument you’ll get against that.

A Great Example in Boise

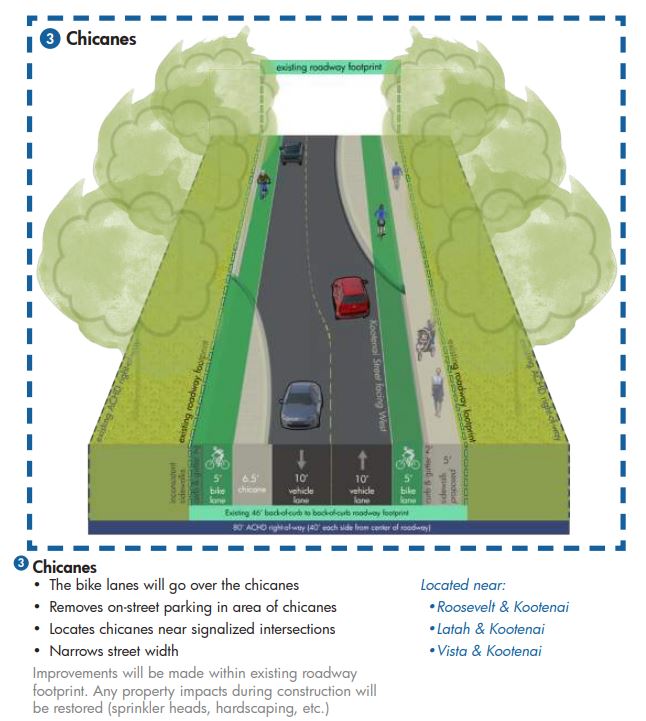

The Ada County Highway District here in Boise recently approved a design concept for Kootenai Street, a collector in a neighborhood known as the Boise Bench. Kootenai a challenging street for safe walking conditions since it was built in an era when sidewalks were not required with new development. It has a curbed section with two vehicle travel lanes, two substandard bike lanes, and two parking lanes. All of those elements are already squeezed into that space.

Building sidewalks at curb level would require removal of dozens of old growth trees that help frame the street and create the type of vertical friction or tunneling effect that helps slow traffic. A typical sidewalk would kill the context and historical feel of the street.

Enough public support emerged in recent years to create better conditions for people who walk along Kootenai, recognizing that parking utilization is low and the street can be reconfigured within its existing curb lines to create a space for people to walk. It’s a vital artery for people who walk and want to access the same destinations motorists want to access on nearby commercial arterials.

The proposed design of the project is easily the best example I’ve seen in recent months of what it means for engineers to promote a “target speed” on a road.

The current posted speed is 25 mph but the 85th percentile analysis showed speeds of 32 mph. ACHD didn’t simply take an 85th percentile analysis and tell the public they must adhere to its findings, as some agencies do, and raise the speed limit. Instead they saw this as a concern and set out to design a road that helped self-enforce the posted speed.

The illustration below shows one concept they’ll deploy on the street: 10 ft lanes, new sidewalks on one side within the existing curb line, and chicanes that shift the vehicle travel lanes from one side to another while preserving a straight line for bicyclists.

As much you see me lampoon ACHD for things like construction zones and weird sharrows, this is a project where they deserve all the accolades and awards the transportation industry can stand to throw at them.

This design embodies so many facets of current Vision Zero thinking. I can’t wait to see it built!

This project also showcases the power of advocacy when it comes to 10 ft travel lanes. The draft report for the project has a great graphic on page 25; one that surprised me.

ACHD had 36 write-in requests to maintain 10-foot travel lanes on the corridor, out of 135 comments received.

Think about that for a second.

Local neighborhood and active transportation folks had enough knowledge on the issue that one out of every four people commenting on the design specifically requested a 10 ft travel lane. I credit this to a very engaged ACHD Commissioner, Jim Hansen, as well as the agency’s bicycle and pedestrian coordinator who helped steer the project toward this design.

Changing the “Standards”

We know a lot more than we did in 1960 or 1970 or 1980 or 1990. The recently-released 7th edition of the AASHTO Green Book is a testament to that, and it provides all the support you need for narrower travel lanes in your community.

In their 2004 Guide for Achieving Flexibility in Highway Design, AASHTO hints at the Green Book being most useful for routes on the National Highway System. They say individual states and cities “have the freedom to develop their own design guidelines and processes based on…local conditions and needs.”

The Kootenai project is an example of a local agency thinking for itself and not taking the maximum lane width values in the Green Book as their standard. In the long run, I hope ACHD sees that this project works and they change their collector street standards to make 10 ft lanes the norm with wider lanes being the exception.

I’ve completed the 12 Days of Safety Myths and I will now enjoy some figgy pudding and several cups of good cheer! Thank you for taking the time to read these. I wish you the best for 2019.

Previous Posts in the 12 Days of Safety Myths Series